For the Audrey Irmas Pavilion at Wilshire Boulevard Temple, Rabbi Steve Leder, senior rabbi of the Los Angeles synagogue, commissioned Rem Koolhaas and Shohei Shigematsu to design a mezuzah to grace the doorways of the new 55,000-square-foot building, a cockeyed honeycomb caught between the historic temple and Brutalist St. Basil Church. As this was OMA’s first religious structure and first mezuzah, neither architect was particularly familiar with the ritual object: a reliclike enclosure for a small scroll inscribed with a prayer. They set about fabricating a design from colored resin and aluminum foam, a material familiar to the office and used to great effect at Fondazione Prada in Milan. Read More …

Reading Countryside, A Report, a book of essays on rural areas by the Dutch architect and his research studio AMO, during the time of Covid-19 is like trying to learn to swim by watching a goldfish.

Produced as a catalogue to accompany the currently shuttered exhibition Countryside, The Future at New York’s Guggenheim museum, the small paperback has a silver foil cover designed by Irma Boom that glints appealingly as it catches the light. The words “Countryside in your pocket! $24.95” advertise an accessible price point.

It would be cliché if it wasn’t true. On a day hazy with smoke from the Woolsey fire, Pritzker Prize-winning Dutch architect and theorist Rem Koolhaas is grumbling about L.A. traffic. Specifically, the two hours it took to get across town on a Friday.

Sitting in the cushy lobby of the Fairmont Miramar Hotel in Santa Monica, Koolhaas is a cautionary futurist. He once called multimodal Los Angeles a prototype habitat for the future of all cities because of its flexibility, networks and mobility.

The gesture was more graceful than the act. With one generous flick of the wrist I sent the paperback sailing across the room. The book, The Age of Earthquakes: A Guide to the Extreme Present, is a small volume tri-authored by an intellectual supergroup: novelist and artist Douglas Coupland, international curator Hans Ulrich Obrist, and cultural critic Shumon Basar. In wry deference to its subject, the cover is inked in an oil slick chromo metallic. As Earthquakes arced from the couch to the closet door, which it hit with a thud before dropping to the floor, light reflected off its glistening surface, giving the appearance of a salmon spawning upstream.

(For the record, S,M,L,XL also boasts a silver cover, but I can’t imagine throwing the six-pound tome very far. Earthquakes, by contrast, is lightweight at 7.8 ounces).

When it landed, facedown, pages splayed and pressed against the floor, the half-light of the living room lamps seemed to illuminate a mysterious object. An alien ship crash-landed on oak boards. And so it sat there for a few days. Until my irritation with leaving a book on the floor trumped my irritation with the book itself and I picked it up. Read More …

In September, Rem Koolhaas stood in front of a bunch of mayors and experts convened in Brussels for the High Level Group meeting on Smart Cities and called them dumb. Not dumb as in stupid, per se, but as these proponents champion a positivist approach they are mute on the real challenges of contemporary cities and deaf to the role of the architect as a shaper of the urban realm.

In the edited transcript of the talk posted online at the European Commission on 3 November, Koolhaas starts out swinging. “I had a sinking feeling as I was listening to the talks by these prominent figures in the field of smart cities because the city used to be the domain of the architect, and now, frankly, they have made it their domain,” he begins, setting up his tweetable one-two punch. “This transfer of authority has been achieved in a clever way by calling their city smart — and by calling it smart, our city is condemned to being stupid.” Read More …

Rem Koolhaas’ Elements of Architecture in the Central Pavilion at the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale opens with a ceiling. Well, two ceilings: the existing, recently restored 1909 dome painted by Galileo Chini and a utilitarian drop ceiling hung at 2.7 meters, complete with electrical and mechanical systems. “One man’s ceiling is another man’s floor,” sang Paul Simon in 1973, some seven years before the first architecture biennale in Venice. A twangy number from a solo album, the song departs from Simon and Garfunkel’s summer of love utopianism and delivers an existential lyric that pivots on the “is,” eluding a single definition a basic architectural element. Koolhaas’ installation might seem like a parody of preservation, a subject he’s known for reconsidering. According to accompanying text, the ceiling is meant to oscillate between symbol and utility pointing out a lingering hang-up of modernization: one man’s iconography is another man’s abstraction. Read More …

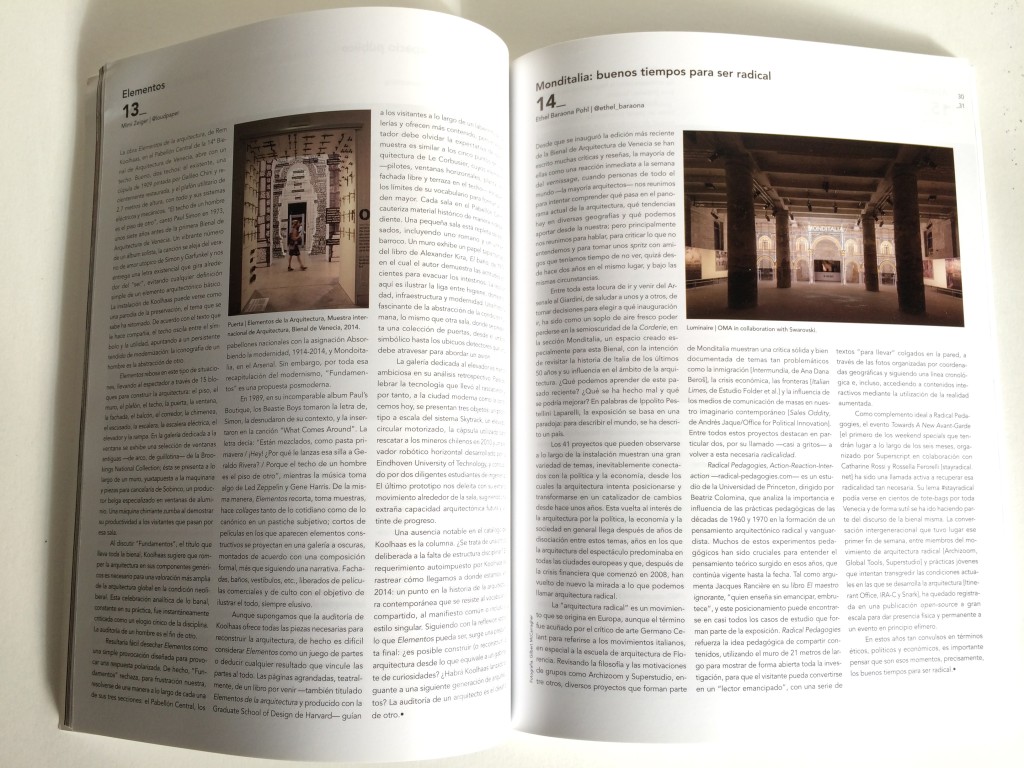

Last Friday, Rem Koolhaas sat on stage in the main event tent of Fundamentals, the 14th International Architecture Exhibition, la Biennale de Venezia, for a panel discussion on preservation. His shoulders were characteristically hunched and his hands were folded over the microphone. All eyes were on Koolhaas as the packed house waited for him to speak, willing him to fully explain why, as director of the biennale, he broke La Biennale into three parts, tasking the national pavilions with a research imperative entitled Absorbing Modernity: 1914–2014, devoting the Central Pavilion to the kit-of-parts Elements of Architecture, and filling the Arsenale with the interdisciplinary, countrywide scan, Monditalia. Read More …

Can a tote bag emblazoned with a hashtag spark change? Over the course of the Venice Biennale vernissage one of the unspoken fundamentals of the Rem Koolhaas-curated exposition, as with any trade show, was the swag bag, the free cotton or nylon tote offered as a token of solidarity between viewer and exhibitor. Of the hundreds of bags carried on the beleaguered shoulders of Giardini visitors, from national pavilion to national pavilion, one stood out – a plain muslin tote bag with the words #STAYRADICAL printed in black ink. Read More …