Rem Koolhaas’ Elements of Architecture in the Central Pavilion at the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale opens with a ceiling. Well, two ceilings: the existing, recently restored 1909 dome painted by Galileo Chini and a utilitarian drop ceiling hung at 2.7 meters, complete with electrical and mechanical systems. “One man’s ceiling is another man’s floor,” sang Paul Simon in 1973, some seven years before the first architecture biennale in Venice. A twangy number from a solo album, the song departs from Simon and Garfunkel’s summer of love utopianism and delivers an existential lyric that pivots on the “is,” eluding a single definition a basic architectural element. Koolhaas’ installation might seem like a parody of preservation, a subject he’s known for reconsidering. According to accompanying text, the ceiling is meant to oscillate between symbol and utility pointing out a lingering hang-up of modernization: one man’s iconography is another man’s abstraction.

Elements luxuriates in these kinds of situations, taking the viewer through fifteen building blocks of architecture: the floor, the wall, the ceiling, the roof, the door, the window, the façade, the balcony, the corridor, the fireplace, the toilet, the stair, the escalator, the elevator, and the ramp. In the gallery dedicated to the window a selection of antique windows—arched, sashed—from the Brookings National Collection is presented along one wall, juxtaposed with machinery and window fittings from Sobinco, a Belgium manufacturer specializing in aluminum windows. A grinding machine sits in the space, whirring its demonstrative productivity to visitors drifting through the room.

In discussing of Fundamentals, the title given to the whole 2014 biennale, Koolhaas suggests that breaking architecture down to its generic component parts is necessary for a larger assessment of architecture in a global, neoliberal condition. This analytic celebration of the banal, a constant in his practice, was instantly criticized as a cynical eulogy for the discipline. One man’s audit is another man’s end.

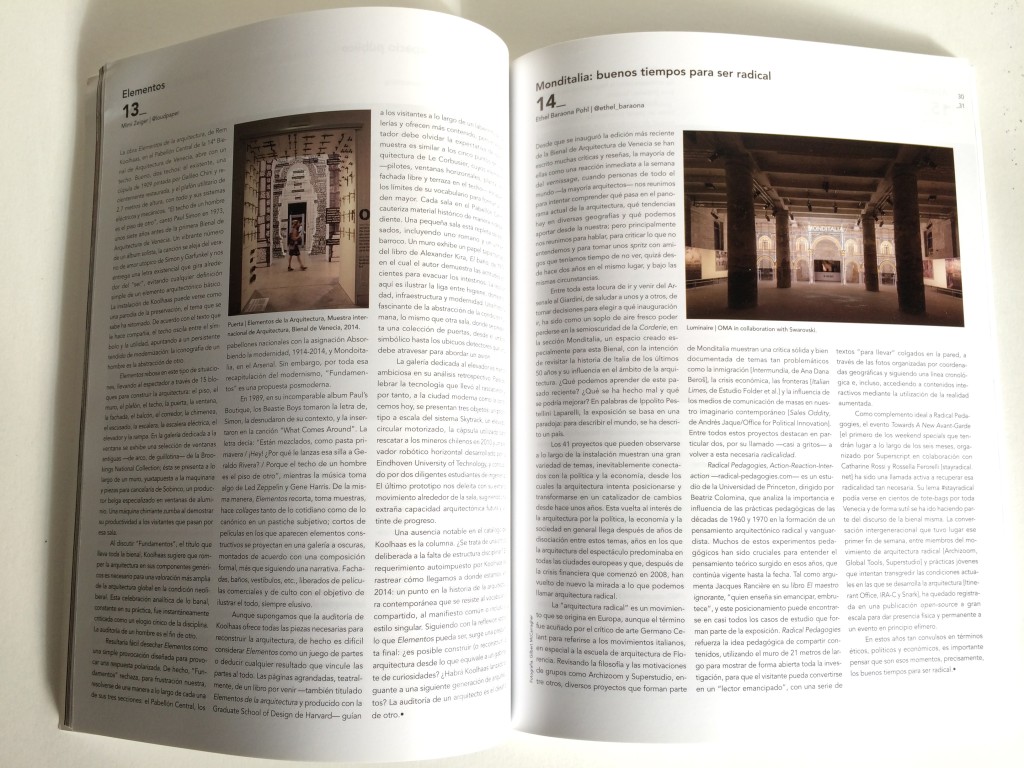

It would be easy to dismiss Elements as simply a provocation designed to illicit a polar response. Indeed, Fundamentals frustratingly refuses to resolve into form across each of its three sections, the Central Pavilion, the national pavilions tasked with Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014, and Monditalia in the Arsenale. For all its recapitulation of modernism, however, Fundamentals is a postmodern proposition.

In 1989 on their matchless album Paul’s Boutique, the Beastie Boys took Simon’s lyric, stripped it of context, and placed it in the song What Comes Around. Their lyrics read: “You’re all mixed up, like pasta primavera/ Yo, why’d you throw that chair at Geraldo Rivera, man?/ Cause one man’s ceiling is another man’s floor” while the music draws from Led Zepplin and Gene Harris. Similarly, Elements clips, samples, and collages both the quotidian and the canonical into a subjective pastiche. Film clips featuring building elements screen in a darkened gallery, montaged together by formal composition rather than narrative. Facades, bathrooms, hallways, etc. were liberated from mainstream and art-house movies for the sake of illustrating the ever-illusive whole.

Although one presumes that Koolhaas’ audit offers up all the pieces needed to rebuild architecture, it is, in fact, it’s difficult to consider Elements as a kit of parts or derive any parts-to-whole outcomes. Theatrical, oversized pages of a forthcoming book—also entitled Elements of Architecture and produced with the Harvard Graduate School of Design—guide visitors through the maze of galleries and offer up additional content, but a viewer has to leave behind any expectation that the show is akin to Le Corbusier’s Five Points of Architecture, where elements—pilotis, ribbon windows, free plan, free façade, and roof garden—escape the boundaries of their vocabulary to form a greater order. Each room in the Central Pavilion independently cauterizes historical material. A small gallery is packed full of toilets, including an ancient Roman commode and a baroque urinal. One wall displays wallpaper taken from Alexander Kira’s 1976 book The Bathroom, in which the author demonstrates efficient attitudes of evacuating the bowels. The lesson here is meant to illustrate the link between the hygiene, domesticity, infrastructure, and modernity. It’s a fascinating history of the abstraction of human condition, just as another gallery displays an array doors from the symbolic gate to ubiquitous body scanners you have to pass through to board an airplane.

The gallery dedicated to the elevator the downplayed the retrospective scan. In celebrating the technology that led to the skyscraper and thus to the modern city, as we know it today, the display featured three objects: a scaled prototype of the Skytrack system, a motorized circular elevator; the capsule used to rescue Chilean miners in 2010; and a robotic horizontal elevator developed by the Technical University of Eindhoven and driven by a pair of dutiful engineer students. The later prototype delights in its awkward movement around the room, suggesting a rare future architectural capability and a glimmer of progress.

Notably missing from Koolhaas’ catalog: the column. Is this a willful critique of a disciplinary lack of structure? Koolhaas’ self-imposed mandate is to track how we got to where we are—2014, a point in contemporary architecture that resists a shared vocabulary, a common manifesto, or, even, a singular style. Still mulling of just what is Elements, a final question arises: Is it possible to build (or rebuild) architecture from what amounts to a cabinet of curiosities? Has Koolhaas thrown down a gauntlet for the next generation of practitioners? One architect’s audit is another architect’s challenge.