“There’s not much difference between fashion design and art,” John Baldessari says laconically. I’ve reached him on the phone of his studio in Venice Beach. Now in his 80s, Baldessari doesn’t go in for trendy theories or prolix sermons. He speaks with the frankness of the L.A. art scene’s elder statesman that he is. “Both are visual mediums. You want to get people’s attention and, generally, you want it to be a pleasant experience. That’s where they overlap.”

Increasingly, Baldessari is wading into this overlap. He’s paired up Rodarte designers Kate and Laura Mulleavy for a magazine cover and a few years ago he created The Giacometti Variations for the Prada Foundation. A play on the fashion show, the exhibition featured artist-designed garments and objects “worn” by a series of fifteen-foot tall, elongated Giacometti-esque sculptures. Occupying several disciplines at once isn’t surprising for an artist whose work often absorbs and recontextualizes commercial imagery and refashions the popular—Buster Keaton film stills or commercial photography—into deadpan critique. He’s collaborated with W and Harper’s Bazaar magazines on spreads. Baldessari treats fashion photography with the same approach as with the found photography he uses in his artworks. “I can’t be rational,” he says of his “interventions”—the application of paint and graphic elements to the photographs: an arrow though the bodice of a model or Karl Lagerfeld pushing a shopping cart, inspired by a Costo-like inventory of sunglasses. “It is about getting people stop and notice more.”

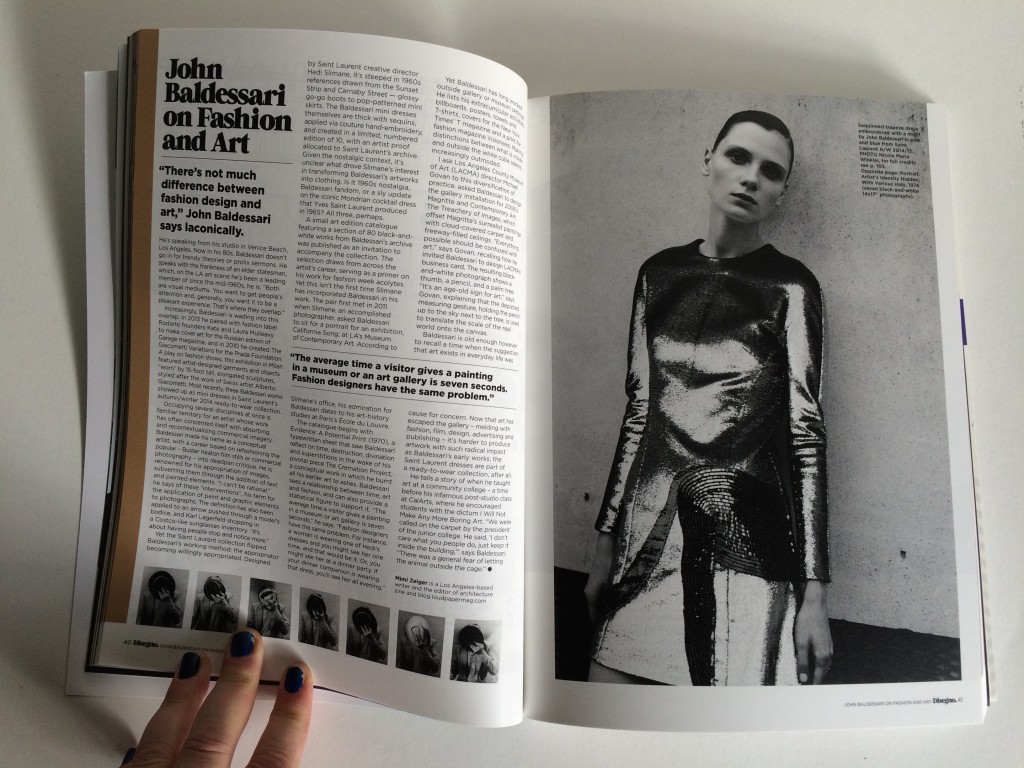

This past spring, in a flip where the appropriator becomes willingly appropriated, three of Baldessari artworks showed up as mini-dresses in Yves Saint Laurent’s Fall 2014 ready-to-wear show. The Fall 2014 collection designed by Hedi Slimane is seeped in 1960s references drawn from the Sunset Strip and Carnaby Street—glossy go-go boots to pop-patterned miniskirts. The Baldessari mini-dresses are thick with sequins, applied via couture hand-embroidery. YSL created a limited and numbered edition of ten, with an artist proof given to the archive. Given the retro context, it’s unclear just what drives Slimane’s interest in the transforming the artworks into clothing. Is sixties nostalgia, Baldessari fandom, or a sly update on the iconic Mondrian cocktail dress Saint Laurent produced in 1965. All three, perhaps.

A small art edition catalog featuring a section of eighty black and white artworks from Baldessari’s archive was published as an invitation to accompany the Fall 2014 collection. The selection draws from across the artist’s career, a primer on his work for fashion week acolytes. This isn’t the first time that Slimane incorporated the artist into his work. The pair first met in 2011 when the designer asked Baldessari to sit for a portrait for a photography exhibition at MOCA entitled “California Song.” According to Slimane’s office, his admiration dates back to his art history studies at the Ecole du Louvres.

The booklet begins with ‘Evidence: A Potential Print’ from 1970, a typewritten sheet upon which Baldessari reflects upon time, destruction, divination, and superstitions in the wake of his pivotal piece ‘The Cremation Project’, in which he burnt his previous works to ashes. Asked how about any relationship between time, art, and fashion, Baldessari finds similarities and, even, a statistical figure. “The average time a visitor gives a painting in museum or an art gallery is seven seconds,” he notes. “Fashion designers have the same problem. For instance, some woman is wearing one of Hedi’s dresses and you might see her one time and that would be it. Or, you might see her at a dinner party—if your dinner companion is wearing that dress, you’ll see her all evening.”

Balessari’s long worked outside of strictly gallery or museum settings. He lists his extracurricular activities: billboards, posters, skateboards, towels, t-shirts. “And on and on and on,” he notes. Currently he’s at work on covers for The New York Times’ T magazine and a print for Visionaire magazine. And as the art world settles into post-conceptual and social practices, making distinctions between what is inside and outside the white cube seems especially outmoded.

I asked Michael Govan, director of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) to weigh in. His institution asked the artist to design the gallery installation for Magritte and Contemporary Art: The Treachery of Images in 2006, which offset the surrealist’s paintings with cloud-covered carpet and freeway filled ceilings. In 2010, LACMA mounted the retrospective John Baldessari: Pure Beauty. “Everything possible should be confused with art,” says Govan, recalling how he called on Baldessari to design the LACMA business card. The black and white photograph shows a thumb, a pencil, and a palm tree. “It’s age old sign for art,” says Govan and explains that the depicted measuring gesture, holding the pencil up to the sky next to the tree, is used to translate the scale of the real world onto the canvas.

Still, Baldessari can remember a time when the suggestion that art exist in everyday life was cause for concern. Now that art has escaped the gallery and melded with fashion, film, design, advertising, publishing, etc. it’s more difficult to produce an artwork with the kind of radical impact of the artist’s early works. The Saint Laurent dresses are part of the ready-to-wear collection, after all. Baldessari tells a story of when he taught art at a small community college—a time before he taught the infamous post-studio class at CalArts. “We were called on the carpet by the president of the junior college, and he said, “I don’t care what people do you, just keep it inside the building,”’ he recalls. “There was general fear of letting the animal outside of the cage.”