Ann Lui and Craig Reschke founded Chicago-based Future Firm in 2015. The practice combines their expertise—Lui co-curated the US Pavilion for the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennial and Reschke is trained as a landscape architect—in order to envision what is on the cultural horizon and to deal directly with critical issues facing neighborhoods and communities in Chicago. Their work spans diverse scales: from events to residential and commercial buildings to urban and territorial speculations, and helps develop unorthodox approaches towards community, belonging, and public engagement in contexts where multiple stakeholders come to the table. Future Firm also currently operates The Night Gallery, a nocturnal exhibition space on Chicago’s South side, which features video and film works by artists and architects from sunset to sunrise. Their work has been exhibited at Storefront for Art & Architecture, New Museum’s Ideas City, and the Chicago Architecture Foundation and published in The Architect’s Newspaper, Chicago Architect, Mas Context and Newcity. They are a 2020-2021 recipient of Exhibit Columbus’ J. Irwin and Xenia S. Miller Prize.

The work of journalist and novelist Annalee Newitz is about what is real and what is fictional, what is past, present, and future. Questions of temporality, urbanism, and identity percolate through Newitz’s science fiction and nonfiction. They are the author of the forthcoming book about archaeology Four Lost Cities: A Secret History of the Urban Age, and the novels The Future of Another Timeline, and Autonomous, which won the Lambda Literary Award. As a science journalist, they are a contributing opinion writer for the New York Times, and have a monthly column in New Scientist. They have published in The Washington Post, Slate, Popular Science, Ars Technica, The New Yorker, and The Atlantic, among others. They are also the co-host of the Hugo Award-winning podcast Our Opinions Are Correct. Previously, they were the founder of io9, and served as the editor-in-chief of Gizmodo.

On February 17, 2009, less than a month after his inauguration, President Barack Obama signed into law the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009. A stimulus bill meant to jump-start the nation’s flatlined economy, the Recovery Act, as it was popularly known, promised nearly $800 million to state and local governments for the funding of “shovel-ready” projects.

The following year, the Ojai, California–based photographer Chad Ress stood on a dry lake bed in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada and watched a tractor maneuver boulders into totemic piles in New Hogan Lake in Valley Springs, California. He was there to document a project funded by ARRA. The resulting photograph is almost boring. The frame captures signs of California’s epic drought; what was once covered in water is now dust. The sky is nearly white. Yet that line of rocks was evidence of money at work.

Imagining a new society begins with visionary design. What can we learn from the bold architectural schemes of the twentieth century?

The frontispiece of the original edition of Sir Thomas More’s Utopia, published in Leuven, Belgium, in 1516, depicts a small island, nearly round with deckled edges. The engraver’s hand shaded the landmass with short, neat hatch marks to suggest topography and a river. More imagined utopia as a self-contained world where communities shared a common culture and way of life. This definition sets up two particular criteria: place and society. To convey these intertwined conditions, the illustrator dotted the woodblock print with buildings.

Born in El Salvador, Los Angeles-based artist Beatriz Cortez crafts sculptures—often large, metal, and architectural—that evoke Latinx and Indigenous pasts and presents. Her practice explores simultaneity, life in different temporalities and different versions of modernity, particularly in relation to memory and loss in the aftermath of war and the experience of migration, and in relation to imagining possible futures. Widely exhibited, Cortez’s has had solo exhibitions at the Craft Contemporary Museum and Clockshop in Los Angeles, and has been included in group shows at the Hammer Museum, the Whitney, and Ballroom Marfa, among others. In 2019 she received the inaugural Frieze LIFEWTR Sculpture Prize and in September 2020, she installed her monumental piece Glacial Erratic in New York City’s Rockefeller Center as part of Frieze Sculpture 2020. In addition to her art practice, she is a cultural and literary critic and professor of Central American Studies at California State University, Northridge. Cortez is the author of Aesthetics of Cynicism: Central American Post War Fiction and the author of numerous essays on postwar Central American literature and culture.

Brooklyn-based visual artist Olalekan Jeyifous creates work that critiques the present by looking at the past and the future. Trained in architecture at Cornell University, he blends techniques and skills from the field with speculation drawn from a range of science fiction imaginaries from Afrofuturism to Solarpunk—a genre that envisions possible ecological futures under climate crisis. Best-known for his digital illustrations in the series Shantytown Megastructures, an imagined Lagos, Nigeria in which contemporary ad hoc construction practices are extrapolated into fantastical vertical settlements, his practice crosses between disciplines and mediums, taking shape as drawings, films, and installations. Jeyifous’ work has been shown at the Shenzhen Biennale of Architecture and Urbanism, the Studio Museum in Harlem, and the Guggenheim Bilbao. His large-scale public artworks were shown at Coachella in 2017 and recently along the waterfront in Alexandria, Virginia. He is one of the participants in the 2020-21 cycle of Exhibit Columbus and the MoMA exhibition, Reconstructions: Architecture and Blackness in America.

Last spring, as stay-at-home orders set in and consumers cleared out store shelves, we learned something that we probably knew all along: You don’t think about toilet paper until you are desperate.

And if the lowly roll is overlooked, the design of the toilet paper holder is even less considered — until now. The Echo Park gallery Marta is presenting “Under/Over,” an exhibition of more than 50 toilet paper holders by an international lineup of artists and designers.

“Reality, however utopian, is something from which people feel the need of taking pretty frequent holidays,” wrote Aldous Huxley in his 1932 dystopian novel Brave New World, and the sentiment is acute nearly 90 years later. The pandemic has intensified and accelerated a digital drift, as culture turns to the virtual— to Zoom, Animal Crossing, or TikTok—for ways to escape and normalize current conditions. Going on a reality holiday, however, risks setting up a needless opposition between activities in our daily lives and our online interactions. The truth is that we are all operating somewhere in between—and it is this middle ground where a number of emerging artists, architects, and designers are staking out territory, using this nonbinary space to address questions of subjectivity and identity.

The works of artist, educator, and social justice activist Corita Kent are packed with slogans and scripture. Her silk-screen posters from the 1960s and ’70s crackle with the energy of a time of social unrest. She pulled text and images from advertising and media, recombining them into compositions reflecting on the Civil Rights and peace movements.

“GET WITH THE ACTION,” demands a 1965 silk-screen titled for emergency use soft shoulder, its primary colors reminiscent of Wonder Bread packaging. “HOPE AROUSES AS NOTHING ELSE CAN AROUSE A PASSION FOR THE POSSIBLE,” says another piece from 1969 in black block letters on a bright-yellow field. Kent’s Pop art style is often compared to that of Andy Warhol— whose paintings of soup cans she saw in 1962 at Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles—often as defense of her legitimate claim to be part of the canon. Yet while the more famous artist traded in a cosmopolitan deadpan, Kent’s practice reflected her Catholic beliefs and humanity.

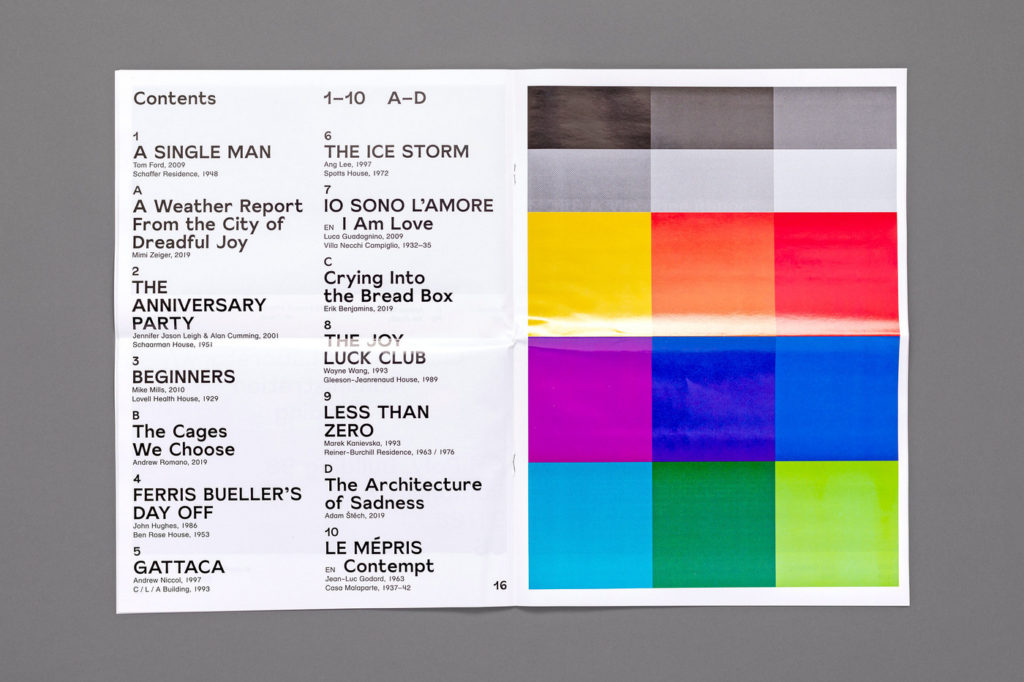

The long-awaited follow-up to the now-canonical ‘Evil People in Modernist Homes in Popular Films’ (2010), ‘Sad People’ examines the filmic trope of housing unhappy characters inside of modernist architecture.

Case studies via ten characters / homes / films, from Colin Firth’s George Falconer inside John Lautner’s Schaffer Residence in Tom Ford’s ‘A Single Man’ (2009) to Brigitte Bardot’s Camille Javal inside Adalberto Libera’s Casa Malaparte in Jean-Luc Godard’s ‘Le Mépris’ (1963).

Essays by Erik Benjamins, Andrew Romano, Adam Štěch (Okolo), and Mimi Zeiger. Ed. by Benjamin Critton.

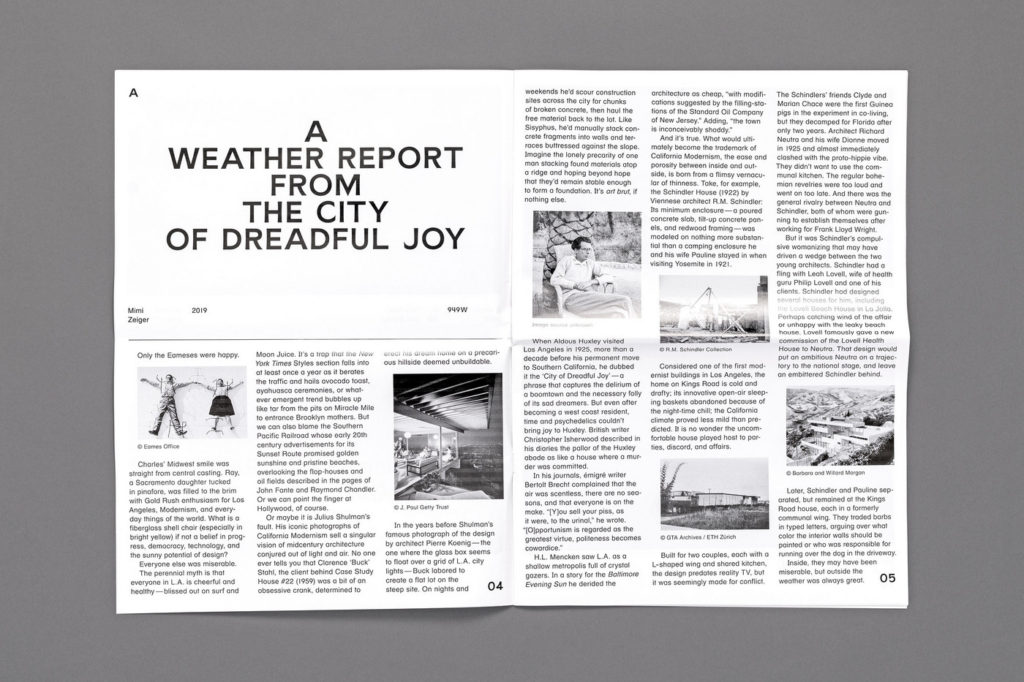

A Weather Report from the City of Dreadful Joy

Only the Eameses were happy.

Charles’ Midwest smile was straight from central casting. Ray, a Sacramento daughter tucked in pinafore, was filled to the brim with Gold Rush enthusiasm for Los Angeles, Modernism, and everyday things of the world. What is a fiberglass shell chair (especially in bright yellow or aquamarine) if not a belief in progress, democracy, technology, and the sunny potential of design?

Everyone else was miserable.