Oakland-based artist Sadie Barnette makes work that is born from her family history — a narrative that is both intensely personal and speaks to a legacy of resistance and opposing societal conditions of racism. Her father, Rodney Barnette, is the subject of much of her work. He was an activist, a member of the Black Panther Party, and later the proprietor of the first Black-owned gay bar in San Francisco. Sadie Barnette’s artworks recontextualize and reimagine these histories, working hundreds of pages of FBI reports into liberatory acts and fantastical objects.

Waste Tide would be a poolside summer read if that pool were toxic swill of first-world effluence. CHEN QUIFAN’s science fiction novel was first published in China in 2013 and he’s currently futurist-in-residence at SCI-Arc. Set amid the e-waste trash heaps of Silicon Isle, a fictional polluted strip of land in a dying sea off the coast of China, the story evokes a future ravaged by climate change choking on obsolete consumer electronics. Modeled in part on the very real town of Guiyu, it’s an uncomfortably recognizable portrait of the Capitalocene and reflection of near-feudal class disparities. In this way, it resonates with novelist and socialist political activist China Miéville’s musings on utopia: “[W]e live in utopia; it just isn’t ours. So we live in apocalypse too.” The twin condition that someone else’s utopia is another’s dystopia is central to Waste Tide’s narrative, but not a foregone conclusion. From the piles of stripped circuity and heavy metal poisons of the dump emerges a worker revolution.

Waste Tide by Chen Quifan and translated by Ken Liu. Tor Books, 2019.

Santa Monica City Hall East deceives with its clean-cut appearance. Sleek and boxy, like a midcentury office building, it features a facade that’s tailored like a gray flannel suit. But the 50,200-square-foot companion to the city’s 1939 Art Deco City Hall is no paper pusher. Behind a bureaucratic exterior lurks a bohemian sensibility and a suite of high-performance green-building systems—including the old countercultural staple: composting toilets.

Read More …

Nearly a decade in the making, its opening pushed back by the pandemic, M+ finally greeted Hong Kong last week. The billboard-like façade of the 700,000-square-foot art museum, designed by Swiss architects Herzog & de Meuron, lit up the budding skyline of the West Kowloon Cultural District with a wall of 5,664 LED tubes. Blue, red, and green from the institution’s logo made watery stripes in Victoria Harbor. Read More …

It’s difficult to think of a building renovation as a riposte. Acts of conservation are generally considered and well-mannered. Conservative by design. And while the newly refreshed Denver Art Museum illustrates such polite attributes, its updates by Machado Silvetti Associates and Fentress Architects are also a sly rebuttal to the Frederic C. Hamilton Building, Daniel Libeskind’s 2006 addition to the museum campus. After years of being thought of as difficult and inhospitable, Gio Ponti’s Lanny & Sharon Martin Building (formerly known as the North Building) is finally pushing back.

When it opened in 2006, Libeskind’s flashy architecture drew attention away from Ponti’s brooding 1971 edifice. Then, in the heady years of the Bilbao Effect’s gestural and populist expressions, the Italian architect’s design was deemed a citadel. Closed off from the city, a bit musty inside, it was branded a bastion of high art at a moment when museum directors, mayors, and developers preached openness.

Genoese architect Renzo Piano would prefer it if you didn’t call the imperial sphere that his firm, Renzo Piano Building Workshop (RPBW), realized for the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures “the Death Star.” Indeed, the Star Warsreference is too on-the-nose for a bulbous structure meant to celebrate Hollywood history. Too self-referential even for an industry that loves a reboot. As if the architecture itself might break the fourth wall and mug for the camera, begging to be blown to smithereens in next year’s biggest blockbuster.

“Call it a dirigible, a zeppelin,” Renzo Piano said correctively to the press ensconced in the plush, red-carpet red, 1,000-seat Geffen Theater, snug in the belly of the monumental vessel (surround sound courtesy of Dolby). Better yet to refer to the 26-million-pound precast concrete, steel, and glass addition to the landmarked May Company building as he does: “a soap bubble.” Read More …

For the Audrey Irmas Pavilion at Wilshire Boulevard Temple, Rabbi Steve Leder, senior rabbi of the Los Angeles synagogue, commissioned Rem Koolhaas and Shohei Shigematsu to design a mezuzah to grace the doorways of the new 55,000-square-foot building, a cockeyed honeycomb caught between the historic temple and Brutalist St. Basil Church. As this was OMA’s first religious structure and first mezuzah, neither architect was particularly familiar with the ritual object: a reliclike enclosure for a small scroll inscribed with a prayer. They set about fabricating a design from colored resin and aluminum foam, a material familiar to the office and used to great effect at Fondazione Prada in Milan. Read More …

What is the aesthetic of nothing? Not in terms of a meditation on minimalism, or the luxury of pared-down colour palettes and clean lines, but nothing itself. How do you design with the fewest possible resources for those who have so little and need so much?

This question rumbles in my head as I get off the 134 Freeway and drive wide, San Fernando Valley boulevards lined with new condo buildings on my way to the Chandler Boulevard Bridge Home Village in North Hollywood – 39 white, red, blue, and yellow tiny homes for the unhoused on a sliver of land between a metro rail line and a busy street. It’s not much of a site, a stingy slice of previously undeveloped municipal property in a sprawling city, but to those who live there it is everything. And it is also nothing. Read More …

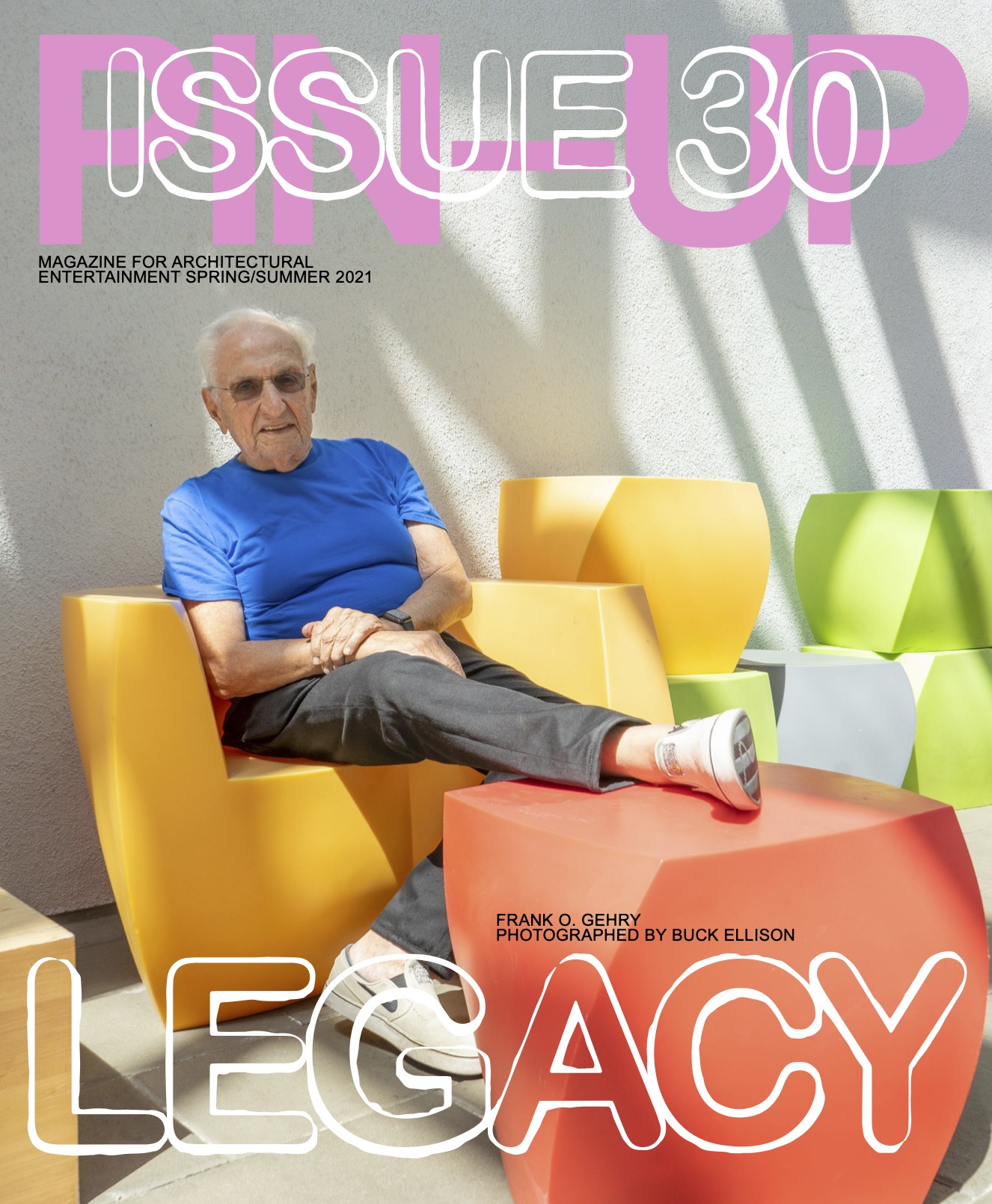

Frank Gehry is arguably the world’s most famous living architect. At 92, does he even require an introduction? Pritzker Prize winner. Iconoclast. Angeleno. His buildings are sculptural and controversial — cultural flash points and crowd-pleasing favorites. Last year, Frank Gehry: Catalogue Raisonné of the Drawings Volume One, 1954–1978, edited by historian Jean-Louis Cohen, was released by Cahiers d’Art. The first of what will be eight career-spanning tomes, the book focuses on early works — designs that predate the titanium and computational dexterity that mark Gehry Partners’ best-known architecture. The 1950s through the 70s were a time of wild growth and experimentation for the architect, from his diploma thesis at the University of Southern California (1954), with its midcentury aesthetic akin to the Case Study Houses and rife with Japanese influences, to Gehry’s own residence in Santa Monica (1978), which exploded any conventional notions of home. The abundant sketches and drawings in the Catalogue Raisonné reinforce an understanding of Gehry as a processes- based architect: iterative and intuitive, rigorously searching for form in what others might see as the arbitrary — methods, perhaps, not dissimilar to those practiced by the cohort of East and West Coast artists he ran with at the time.

If you design a different type of medical school, will it produce a different type of doctor?

This question is at the heart of the Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine, which opened its doors in July 2020, smack in the middle of the pandemic. The 50 students in the inaugural class are, by default, part of an experiment that hopes to integrate an education that highlights well-being and holistic care, an emphasis on social justice, and a new vertical campus that embodies these approaches.