The demise was probably inevitable, foretold by an Ed Ruscha painting. William Pereira’s LACMA opened in 1962, but the buildings were never great. Its corporate modernism was inward‑looking, and its flourishes didn’t age well. Later additions by Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Associates (1986) and Renzo Piano (2008, 2010) atomised the campus, but there was always something pleasant about sitting in the plaza and watching museum‑goers drift from building to building – a piece of pedestrian urbanism in a town long blasted for not having any. (It does.)

Out of the windows of Lenny Steinberg’s Venice Beach living room, there are a few hundred metres of sand, a line of white surf, then the grey-blue expanse of the Pacific Ocean. It’s a remarkable, pinch-me view, the kind most folks only see from the nearby boardwalk at Muscle Beach, where tourists and roller skaters glide through a perfume of cannabis dispensaries and fish taco stands.

The LA-based designer’s home is just a few doors down from Frank Gehry’s Norton House, a mid-1980s landmark that mimics a lifeguard tower. She and her husband, Bob, a prominent lawyer, moved here in the 1990s, transforming a 1960s post-and-beam duplex into a minimalist roost that now houses an archive and showroom of five decades of her work, alongside her art and object collection. Each piece – from the Lucite high heels on a table by the front door to the Frank Stella print in the main bedroom – reflects, in short, the fruits of a highly creative life.

Lesley Lokko’s sprawling, dense Biennale asks us to engage different representational languages. It’s a slow burn, but finding new legibility takes a moment.

“Zt. Zzt. ZZZzzzZZZzzzzZZZzzzzzzZZZZzzzzzzzzZZZzzzzzZZZzzzzo’ona,” begins The Old Drift, Namwali Serpell’s 2019 novel set in Zambia. The insistent whine of a mosquito. Her pesky, omniscient narrator traverses generations and geographies. It’s a tale of violence and the folly of colonization. That hum, indigenous and persistent, singular and swarm, is the consciousness of the African continent.Those ZZZs droned through the Arsenale and Giardini as participants, journalists, and VIPs gathered to kick off the eighteenth International Venice Architecture Biennale, and echoed across alleys and piazze made damp by unseasonal rain and high tides. Venice, after all, is a reformed swamp with mosquitos of its own.

Much has been said about how we live in a time of acceleration. We strive for fast and interconnected. And yet, a considerable body of discourse takes the counter position, arguing for rest, care, and immobility. In her 2019 book How to Do Nothing, Jenny Odell urges us to turn away from the churn, writing, “Our very idea of productivity is premised on the idea of producing something new, whereas we do not tend to see maintenance and care as productive in the same way.”

Architecture, too, is caught in the thrall. Although buildings take time, we’re junkies for novelty. Museumbuildings are particular eye candy. Supposed freedoms of art and culture push desires for formal inventiveness. But what would it mean to construct a museum in slow motion?

An anachronistic exoskeleton design first conceived in 1999, resurrected in 2006, and now looming over the Expo line, it’s impossible to look at the baroquely formalist (W)rapper tower without gagging on certain circumstances surrounding its rise: an evaporating market for any office space much less the lofty double- and triple-height ceilings on offer and ERIC OWEN MOSS’s tenure as SCI-Arc director and the inflated high six-figure salary he pocketed. (W)rapper encapsulates architecture not as autonomous form but as a succubus that extracts everything from tuition to natural resources.

“This is the beginning of a cultural institution,” said Morphosis principal Thom Mayne in late September, seated in the plaza of the nearly completed Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA), in Costa Mesa, California. Behind him, VIPs dressed in black tie streamed from the valet to the white-on-white lobby for an exclusive opening event on the structure’s upper terrace. The $94 million building—its swooping prow jutting like a glazed pompadour from the facade—opened to the public on October 8.

Located at Segerstrom Center for the Arts, a suburban campus studded with architecture by Pelli Clarke Pelli and Michael Maltzan Architecture, Morphosis’s 53,000-square-foot museum is the last piece of a plan devised by civic leaders and philanthropists in the late 1960s and begun in the ’80s. It was designed to cluster Orange County’s arts organizations—like a food court for culture where you can catch the symphony, a touring production of Hamilton, and now an art exhibition.

The Architecture of Disability uses the lens of disability to reevaluate received architectural histories and speculate on a more inclusive architectural environment.

A shock of recognition comes early in The Architecture of Disability. Author David Gissen argues in his introduction that while providing adequate access for disabled people is necessary, making it the dominant principle by which architecture responds to impairment not only is insufficient but also reinforces alienating functionalist narratives. And then, toward the end of this initial essay, he turns the mirror on the discipline itself—to the hustles of studio, site visits, and archival work that compose common design and research practices. In short, the ways that architecture cultivates an unwritten doctrine of, as Elon Musk might put it, hard core. Read More …

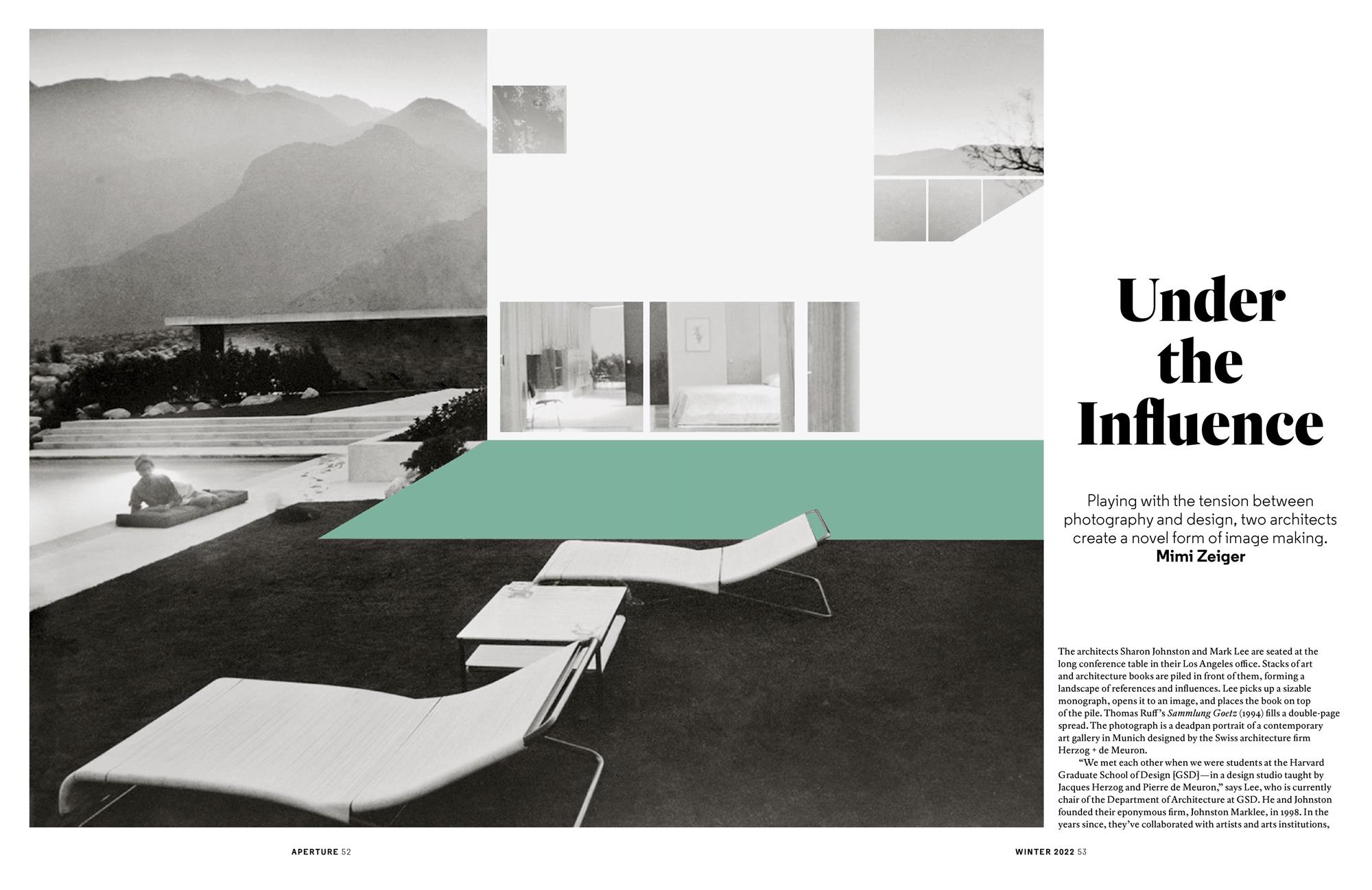

The architects Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee are seated at the long conference table in their Los Angeles office. Stacks of art and architecture books are piled in front of them, forming a landscape of references and influences. Lee picks up a sizable monograph, opens it to an image, and places the book on top of the pile. Thomas Ruff’s Sammlung Goetz (1994) fills a double-page spread. The photograph is a deadpan portrait of a contemporary art gallery in Munich designed by the Swiss architecture firm Herzog + de Meuron.

Tras una década en desarrollo, el viaducto de la Calle Sexta de Los Ángeles abrió al público a principios de julio de 2022 entre fanfarria y caos. Diez pares de arcos de concreto, cada uno inclinado expresivamente hacia afuera 9 grados, se iluminaron con luces LED azules y rojas. El alcalde de Los Ángeles, Eric Garcetti, se unió a políticos locales y al arquitecto del puente, Michael Maltzan, para el corte de listón y los eventos de apertura que dieron la bienvenida a los residentes de Los Ángeles para ocupar la carretera de poco más de 1 kilómetro de largo antes de que se llenara de tráfico de automóviles.

Construido en 1932, el puente art déco original fue demolido en 2016 debido al deterioro de su integridad estructural, causado por reacciones de álcali-sílice, o “cáncer del concreto”. Su reemplazo es un viaducto atirantado con un costo de $588 millones que cruza el río L.A., uniendo el canal de concreto que se hizo famoso en películas como Terminator 2: Judgment Day y Repo Man. A medida que la carretera conecta el vecindario de Boyle Heights con el Arts District, anteriormente industrial y ahora gentrificado, sus arcos saltan sobre 18 pares de vías férreas y la autopista US 101. Durante el fin de semana inaugural, un desfile de relucientes lowriders avanzó lentamente por la plataforma, una representación de la cultura chicana de Boyle Heights.

In 2002, the artist hoped her 63-square-foot cabin—temporary, portable, and made out of aluminum-framed fiberglass panels—would help make the High Desert an art destination outside of Los Angeles.

Andrea Zittel is a homebody. The artist, who finds herself globetrotting from Berlin to Brooklyn or from the California high desert to Stockholm, maintains two residences that double as laboratories for her artwork. A-Z East is in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn and A-Z West is two hours outside of Los Angeles, in the town of Joshua Tree.