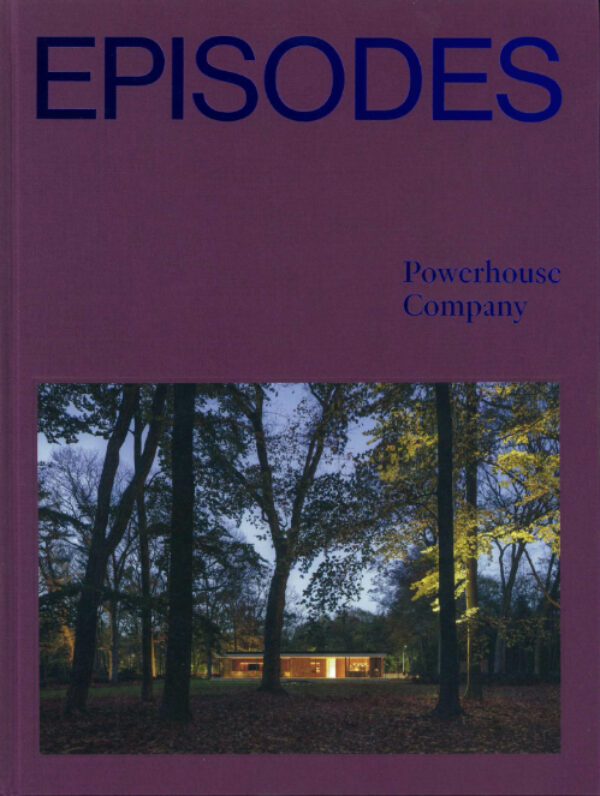

With 18 projects ranging from a chair to high-rise buildings, this book offers a cross section of the recent work of Powerhouse Company, which is based in Rotterdam, Munich, and Oslo. These projects are episodes in the success story of an architectural office that only completed its first building, a villa, in 2007. In three essays, Mimi Zeiger, Hans Ibelings, and Gay Gassmann share their insights on the work and the motivations of Powerhouse Company. Episodes traces how Powerhouse Company’s architecture has evolved while retaining what sets it apart: its attention to craftsmanship and innovation, its generosity, its comfort, and its resolute beauty.

An anachronistic exoskeleton design first conceived in 1999, resurrected in 2006, and now looming over the Expo line, it’s impossible to look at the baroquely formalist (W)rapper tower without gagging on certain circumstances surrounding its rise: an evaporating market for any office space much less the lofty double- and triple-height ceilings on offer and ERIC OWEN MOSS’s tenure as SCI-Arc director and the inflated high six-figure salary he pocketed. (W)rapper encapsulates architecture not as autonomous form but as a succubus that extracts everything from tuition to natural resources.

“This is the beginning of a cultural institution,” said Morphosis principal Thom Mayne in late September, seated in the plaza of the nearly completed Orange County Museum of Art (OCMA), in Costa Mesa, California. Behind him, VIPs dressed in black tie streamed from the valet to the white-on-white lobby for an exclusive opening event on the structure’s upper terrace. The $94 million building—its swooping prow jutting like a glazed pompadour from the facade—opened to the public on October 8.

Located at Segerstrom Center for the Arts, a suburban campus studded with architecture by Pelli Clarke Pelli and Michael Maltzan Architecture, Morphosis’s 53,000-square-foot museum is the last piece of a plan devised by civic leaders and philanthropists in the late 1960s and begun in the ’80s. It was designed to cluster Orange County’s arts organizations—like a food court for culture where you can catch the symphony, a touring production of Hamilton, and now an art exhibition.

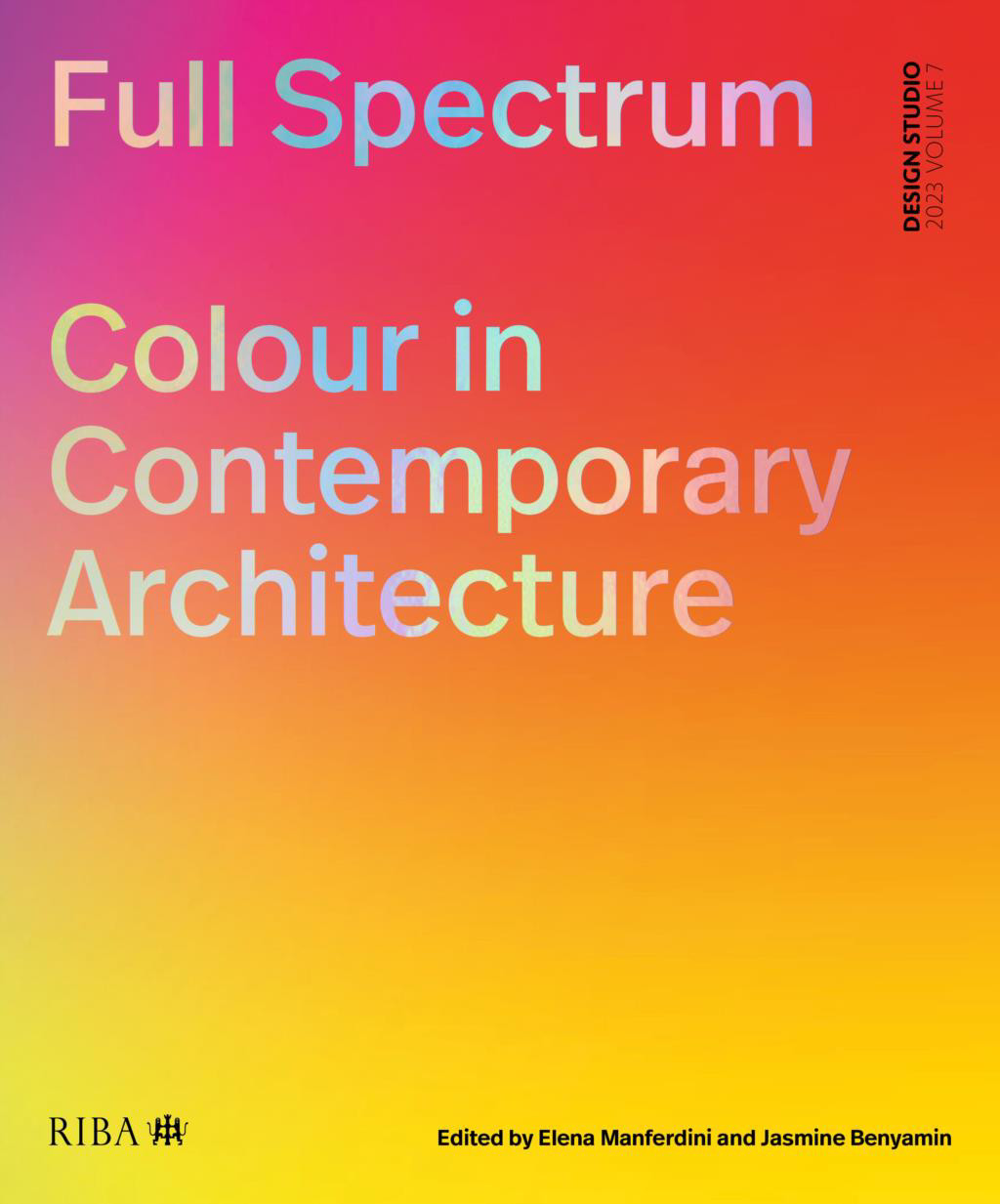

Colour is architecture’s sharpest tool in the box. It has indexed everything from the feminine, cosmetic and vulgar to the pure, intrinsic and embodied.

Attitudes to colour are constantly shifting. They have played a central role in the history of architecture: from the polychromy of the ancients to the great white interiors of high modernism; the figurative flourishes of postmodernism to the embodied sublime of contemporary building systems and facades.

The Architecture of Disability uses the lens of disability to reevaluate received architectural histories and speculate on a more inclusive architectural environment.

A shock of recognition comes early in The Architecture of Disability. Author David Gissen argues in his introduction that while providing adequate access for disabled people is necessary, making it the dominant principle by which architecture responds to impairment not only is insufficient but also reinforces alienating functionalist narratives. And then, toward the end of this initial essay, he turns the mirror on the discipline itself—to the hustles of studio, site visits, and archival work that compose common design and research practices. In short, the ways that architecture cultivates an unwritten doctrine of, as Elon Musk might put it, hard core. Read More …

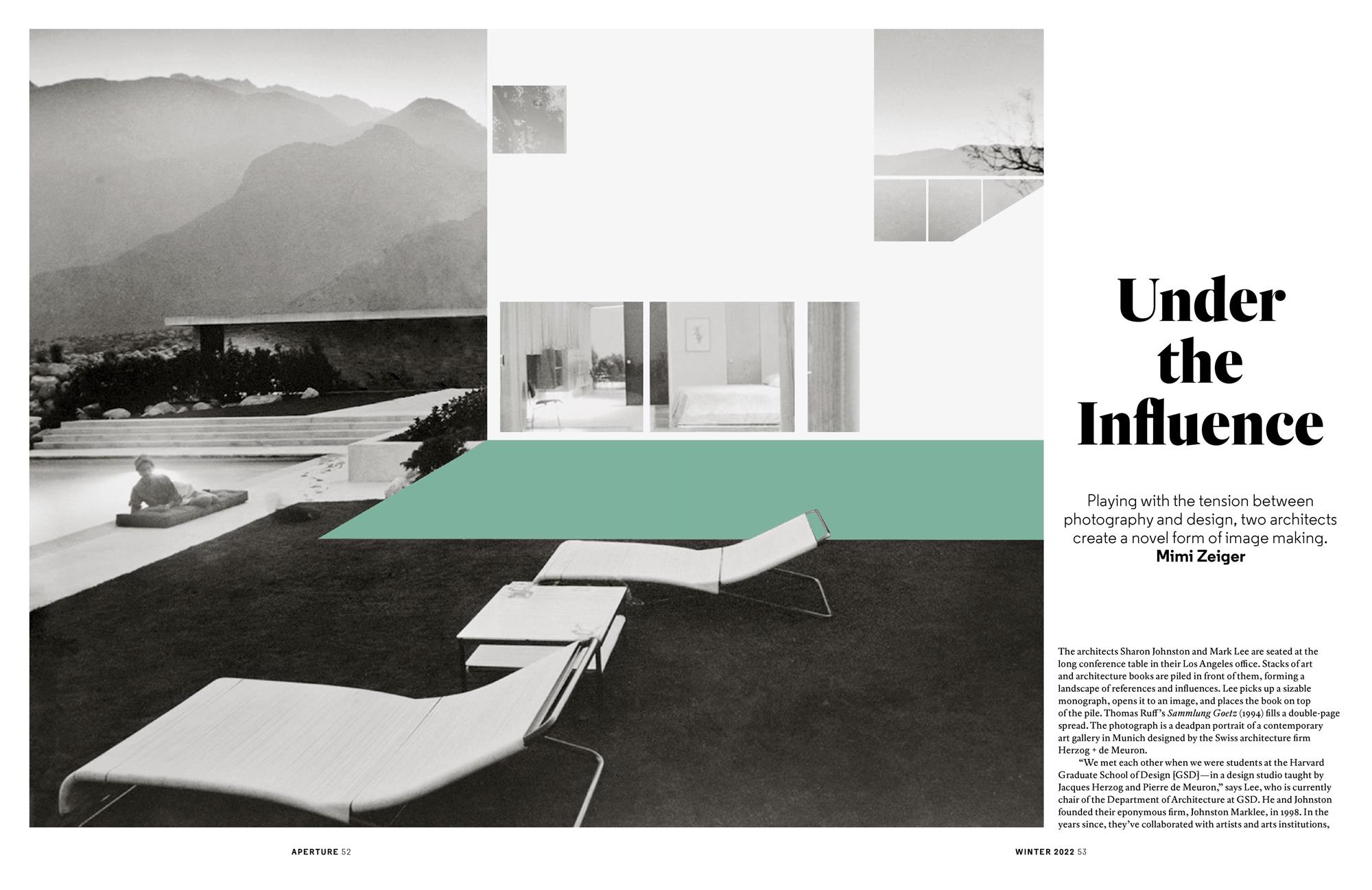

The architects Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee are seated at the long conference table in their Los Angeles office. Stacks of art and architecture books are piled in front of them, forming a landscape of references and influences. Lee picks up a sizable monograph, opens it to an image, and places the book on top of the pile. Thomas Ruff’s Sammlung Goetz (1994) fills a double-page spread. The photograph is a deadpan portrait of a contemporary art gallery in Munich designed by the Swiss architecture firm Herzog + de Meuron.

Tras una década en desarrollo, el viaducto de la Calle Sexta de Los Ángeles abrió al público a principios de julio de 2022 entre fanfarria y caos. Diez pares de arcos de concreto, cada uno inclinado expresivamente hacia afuera 9 grados, se iluminaron con luces LED azules y rojas. El alcalde de Los Ángeles, Eric Garcetti, se unió a políticos locales y al arquitecto del puente, Michael Maltzan, para el corte de listón y los eventos de apertura que dieron la bienvenida a los residentes de Los Ángeles para ocupar la carretera de poco más de 1 kilómetro de largo antes de que se llenara de tráfico de automóviles.

Construido en 1932, el puente art déco original fue demolido en 2016 debido al deterioro de su integridad estructural, causado por reacciones de álcali-sílice, o “cáncer del concreto”. Su reemplazo es un viaducto atirantado con un costo de $588 millones que cruza el río L.A., uniendo el canal de concreto que se hizo famoso en películas como Terminator 2: Judgment Day y Repo Man. A medida que la carretera conecta el vecindario de Boyle Heights con el Arts District, anteriormente industrial y ahora gentrificado, sus arcos saltan sobre 18 pares de vías férreas y la autopista US 101. Durante el fin de semana inaugural, un desfile de relucientes lowriders avanzó lentamente por la plataforma, una representación de la cultura chicana de Boyle Heights.

The Grand LA is the last lot on Los Angeles’ Grand Avenue to be developed. Located across the street from the iconic Walt Disney Hall Concert Hall on a slope pitched toward City Hall, its site was once a parking lot for jurors heading to the nearby courthouse. For decades, as it sat underutilized and as new office buildings and cultural institutions piled up in Downtown L.A.’s Bunker Hill neighborhood, the plot—a centerpiece of the so-called Grand Avenue Project master plan—represented pure potential. Could another piece of esteemed architecture finally pull together this mismatched Acropolis and make it the kind of civic destination so desperately envisioned by late philanthropist Eli Broad and city planners?

Spoiler alert: Nope.

In Frank Gehry’s oeuvre there are the big, career-defining projects—like Walt Disney Hall and the Louis Vuitton Foundation—and there are the minor works: buildings that have smaller footprints and more humble design ambitions but are fortified with good intensions. Gehry Partners has been dabbling in this latter category of late, first with the Beckmen YOLA Center, a community center and youth music conservatory built for the LA Phil’s youth orchestra housed in a retrofitted bank building in Inglewood, and recently, a new 20,000-square-foot campus for Children’s Institute in Watts.

The firm provided architectural services pro bono to the 100-year-old support organization, which addresses poverty and health inequity. It’s an imprimatur that is as much philanthropic as it is architectural—perhaps even more so, as Gehry’s name conveys instant recognition to board members and donors. “The Children’s Institute is about helping families who are victims of trauma and violence,” said Sam Gehry, associate at Gehry Partners and Frank’s son. “[Its mission] is something that we are passionate about.”