I’m not going to define history. No matter how heavily that word weighs on the Chicago Architecture Biennial, which opened last weekend. Neither will artistic directors Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee; although they provocatively titled the second iteration of the event “Make New History”, a phrase borrowed from the title of an artist book by Ed Ruscha.

In remarks to the press, they pointed to the many works displayed in the Chicago Cultural Center as explanation. And if these works are to be trusted, then history is not the dark angel haunting philosophers and historians, but rather something lighter: a shiny treasure trove of references – called forth by Google image search – to be appropriated and stylised.

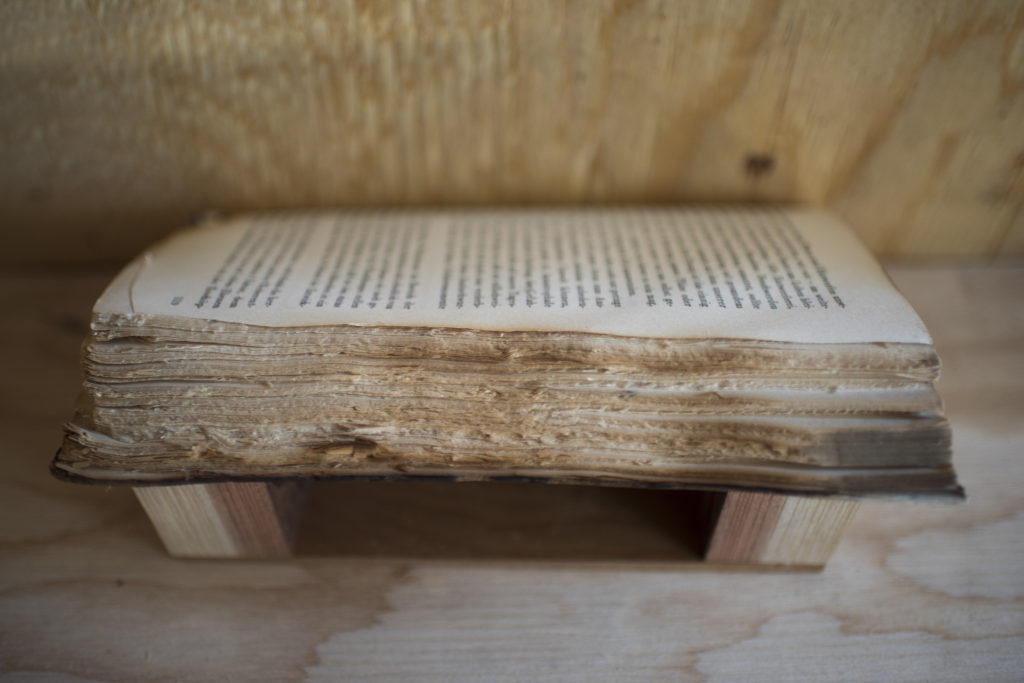

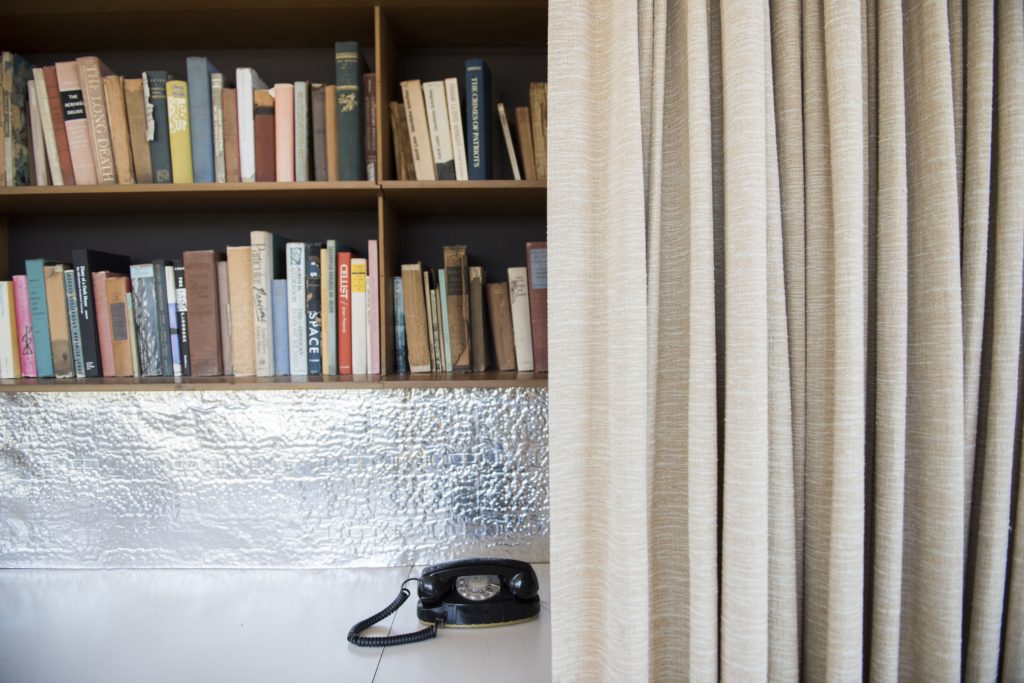

Deadpan Ruscha understood the irony of his slogan. With three simple words he poked fun at the impossibility of escaping our past. An edition of Make New History sits on the shelves of Johnston Marklee‘s office (or so says editor Sarah Hearne in her introduction to the biennial catalog). Read More …