The architects Sharon Johnston and Mark Lee are seated at the long conference table in their Los Angeles office. Stacks of art and architecture books are piled in front of them, forming a landscape of references and influences. Lee picks up a sizable monograph, opens it to an image, and places the book on top of the pile. Thomas Ruff’s Sammlung Goetz (1994) fills a double-page spread. The photograph is a deadpan portrait of a contemporary art gallery in Munich designed by the Swiss architecture firm Herzog + de Meuron.

“We met each other when we were students at the Harvard Graduate School of Design [GSD]—in a design studio taught by Jacques Herzog and Pierre de Meuron,” says Lee, who is currently chair of the Department of Architecture at GSD. He and Johnston founded their eponymous firm, Johnston Marklee, in 1998. In the years since, they’ve collaborated with artists and arts institutions, designing new buildings for the Menil Drawing Institute, in Houston, and the UCLA Margo Leavin Graduate Art Studios, in Culver City, where Catherine Opie is chair of the UCLA Department of Art. As artistic directors of the 2017 Chicago Architecture Biennial, they included works by the photographers James Welling and Filip Dujardin, among others.

Johnston and Lee saw Ruff’s photographs of their professors’ work at an exhibition at Peter Blum Gallery in New York in 1994. At the time, the pair were compelled by the photograph’s flatness—a quality they explore in their own work. And they are still drawn to it because, despite being a representation of a building, it defies conventional notions of objectivity.

Banal at first glance, Sammlung Goetz shows a beige box set against a mossy lawn and gray-blue sky. The flat, frontal composition hearkens back to the typology series of industrial buildings by the German photographers Bernd and Hilla Becher, whom Ruff studied under at the Kunstakademie Dusseldorf. But this is not a single, perfect frame. The photograph was retouched to remove trees in the foreground and pieced together from several images taken at different times. Cast in shadow with a faint pattern of reflections in the glass, the facade was photographed during the day, but in the lower left, the glass seems to disappear and the library glows warmly from within—like a nighttime nativity scene.

In a 1996 Artfomm review, Daniel Birnbaum called attention to this manipulation—one both technical and emotional—writing, “In much of his production Ruff seems to want to question the camera’s status as a reliable witness.” Troubling what is and what isn’t real could suggest multiple perspectives. But what might be more interesting in a discussion of architecture is understanding the photograph as a collage of multiple temporalities, evoking the way we experience buildings in both time and space. “It’s a collage, so it’s not actually a ‘true’ photograph,” says Johnston. “The image exists outside of pure documentation and starts to have a narrative unto itself that talks conceptually about the project.”

That Sammlung Goetz represents both a semi-truth of a building and an alternative narrative echoes a long-standing point of discussion about the photographing of architecture. Is it simply documentation, architectural photography as marketing for a firm’s work, or is it, well, art—an artistic composition open to the vicissitudes of meaning? The architecture historian Claire Zimmerman draws a distinction between the former and what she calls “photographic architecture,” or the early twentieth-century influence of the camera on the architecture. “The visual practices that were part of photography entered into the design procedures of architects, resulting in new architectural concepts that were manifested in constructed projects,” she wrote in her 2014 book, Photographic Architecture in the Twentieth Century. The history of the relationship between the two fields is one of codependence. And like all relationships, there are tensions. Grounded in its own solidity, architecture relies on the camera for the kind of freedom an edifice can never really offer. It is only through the prolific photographic image that architecture might achieve the lightness necessary for media mobility and wide-reaching influence.

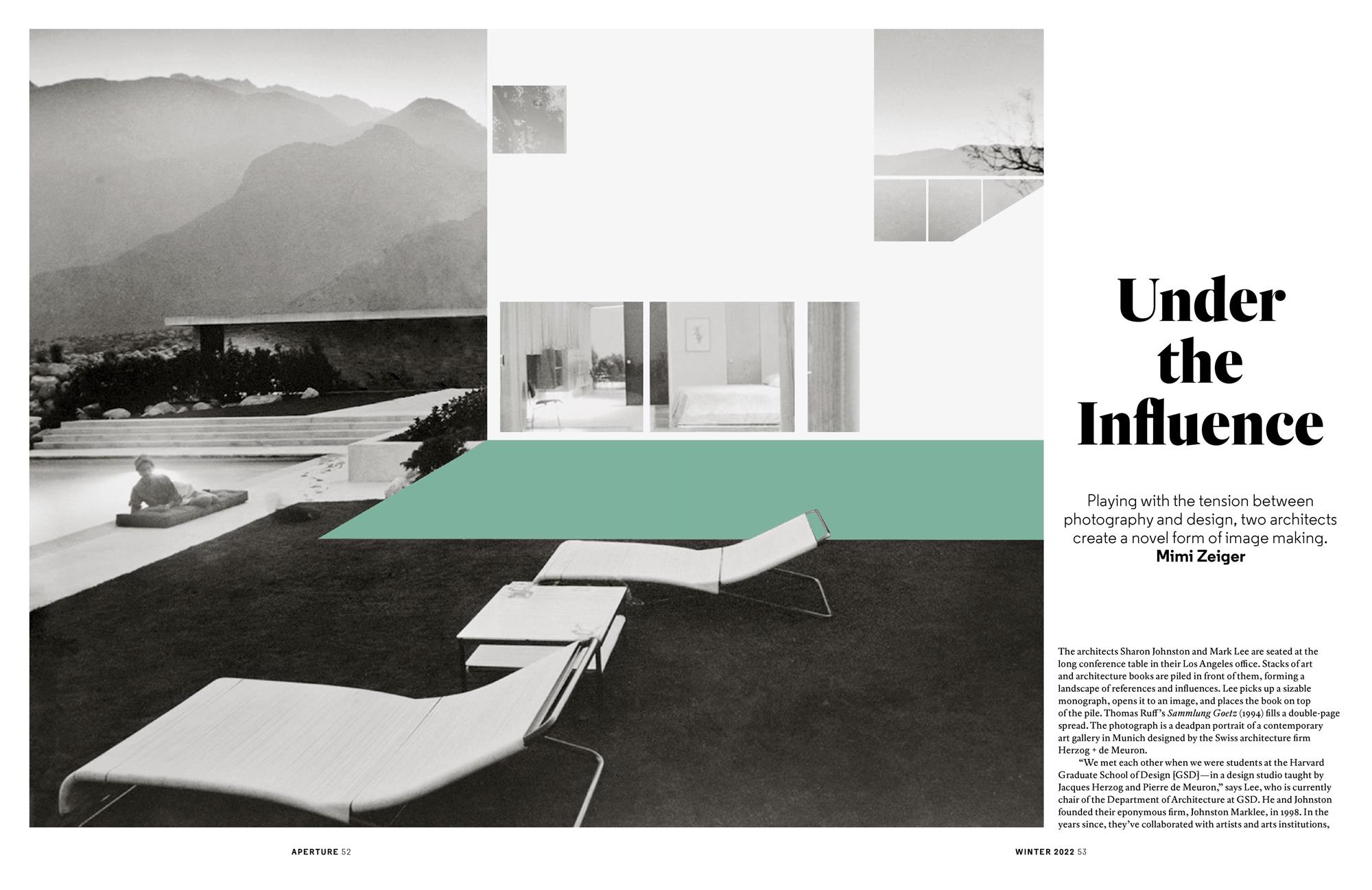

Johnston and Lee like to play with these tensions. They appropriated Julius Shulman’s i960 photograph of midcentury LA architecture Case Study House No. 22, and inserted his famous view into their collage study of Hill House (2002-4), a Pacific Palisades home designed by their firm. The spare details of Case Study House No. 22’s glass box were stripped away, leaving its two women in flouncy dresses to perch over the Los Angeles Basin supported only by abstracted geometries.

It is only through the prolific photographic image that architecture might achieve the lightness necessary for media mobility.

In telling the story behind Shulman’s iconic photograph in Los Angeles Magazine, the author Mary Melton described how, as part of the Case Study House program sponsored by Arts & Architecture magazine, discounts on building materials were given to the homeowners in exchange for having Shulman’s photographs run in the magazine, as publicity. “Not only did the photograph depend on the house, but the house depended on being photographed,” wrote Melton.

Johnston Marklee’s collage, by extension, shares in this sense of interdependency. By incorporating the photograph, arguably Shulman’s most widely published and recognizable, they willfully capture the midcentury cultural cool and attendant historical references that define the image. Johnston and Lee have used this approach with film and photography across numerous projects, including incorporating other of Shulman’s images, but sometimes the connection to sociopolitical context is more ambiguous.

For example, the architects’ collage for their Grand Traiano Art Complex (2007-9) includes an image of Casa del Fascio (1932-36), the former Fascist headquarters in Como, Italy, by the modernist architect Giuseppe Terragni. Within architecture circles, the best-known photograph of Casa del Fascio depicts the Piazza del Popolo brimming with people and the building behind. Yet, like Ruff’s artwork, this image has been manipulated, and the objective, documentary truth is hazy. When the architect Peter Eisenman published his research on Terragni in the early 1970s, he removed the large Fascist banner draped over the facade in the original photograph. Johnston Marklee’s collage is a subsequent adaptation of Eisenman’s alteration, in which they replaced the original structure with one of their own but kept the audience, in a suggestion of urban theater.

Photography “was a projective tool that helped us see the work in a way no other medium would do,” recalls Johnston. Ultimately, the firm’s architectural designs find their own narratives. For the Hill House project, however, the trajectory loops in on itself. In 2002, the then-unbuilt house won a prestigious Progressive Architecture Award, but in order for the architects to publish their collage, they required copyright permission from Shulman, who was in his nineties at the time. Shulman granted the rights, but he wanted to photograph the finalized Hill House— and even, according to Lee, brought his own Harry Bertoia sculpture to stage the shoot.

“We were interested in the whole cyclical aspect,” adds Lee. “That’s when we started commissioning artists to interpret our work beyond the typical architectural photography for documentation.” Johnston Marklee invited eight artists to photograph the firm’s residential projects for their 2016 monograph, House Is a House Is a House Is a House Is a House (the title another detournement). An untitled photographic series of the Hill House by the Italian artist Louisa Lambri focuses on the discrete corner conditions of the exterior—the places where light and shadow come together in a crisp line. As abstraction, her images convey the starkness of the architects’ geometries, yet within the frame, materialist details that might go unseen are revealed: the shadow cast by dry grasses, or the uneven texture of white stucco under the Southern California sun. Jack Pierson’s portfolio of the Vault House (2008-13) is similarly divided between the abstract and the mundane. While his compositions of the swoops of the white roof against the blue sky celebrate architectural expression, his photograph of a pale-green garden hose curled on the home’s beachfront terrace suggests the homely rituals of everyday life generally hidden from the camera.

“We wanted to see something new through their eyes,” says Johnston. “I think that letting go of control is exciting.”

For her and Lee, collaborating with photographers over the years has encouraged them to conceptualize their work differently: to lean into moments of interpretation, to think of architecture as a scaffold for activity rather than a prescription. “There’s a high degree of specificity in our work, but there’s also a sort of underdetermined quality,” she adds. “Anything can happen in the spaces.”