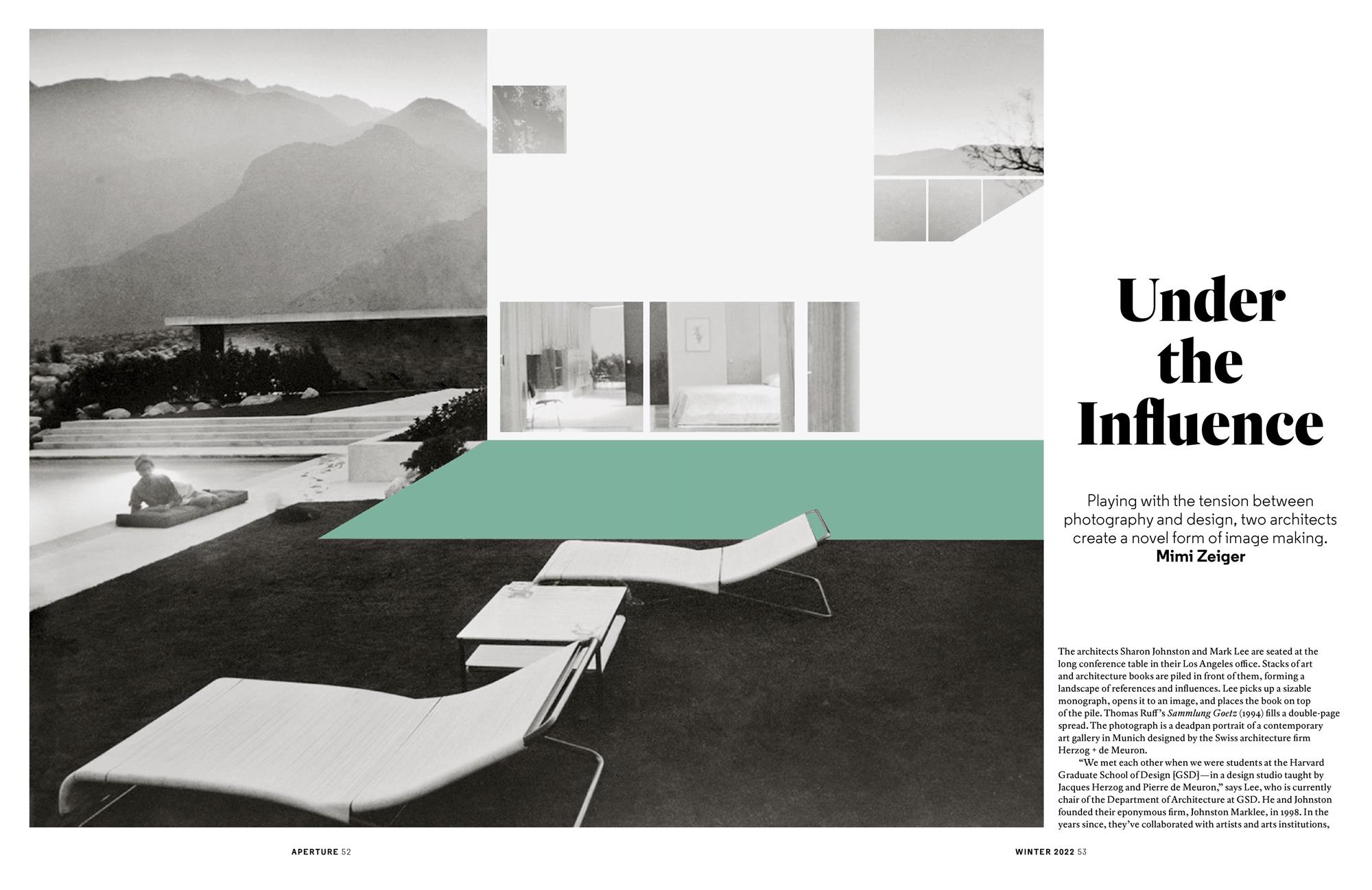

By valuing small spaces, we find pleasures through design more generous and more humane than solutions made for bigger projects—adding to the case for living with less.

This past summer, Barbie Dreamhouses sprawled out across our collective imagination like a rose-colored suburban subdivision. They feature prominently in Greta Gerwig’s movie, where a solitary Barbie occupies each multistory home. Notably wall-less and stair-less (who needs a staircase when a spiral slide will do?), the toy houses reflect vast expansiveness—in pink. Boundless, they combine manifest destiny, the American dream, and a pop feminist utopia. If Virginia Woolf wanted a room of one’s own, Barbie craves the world.