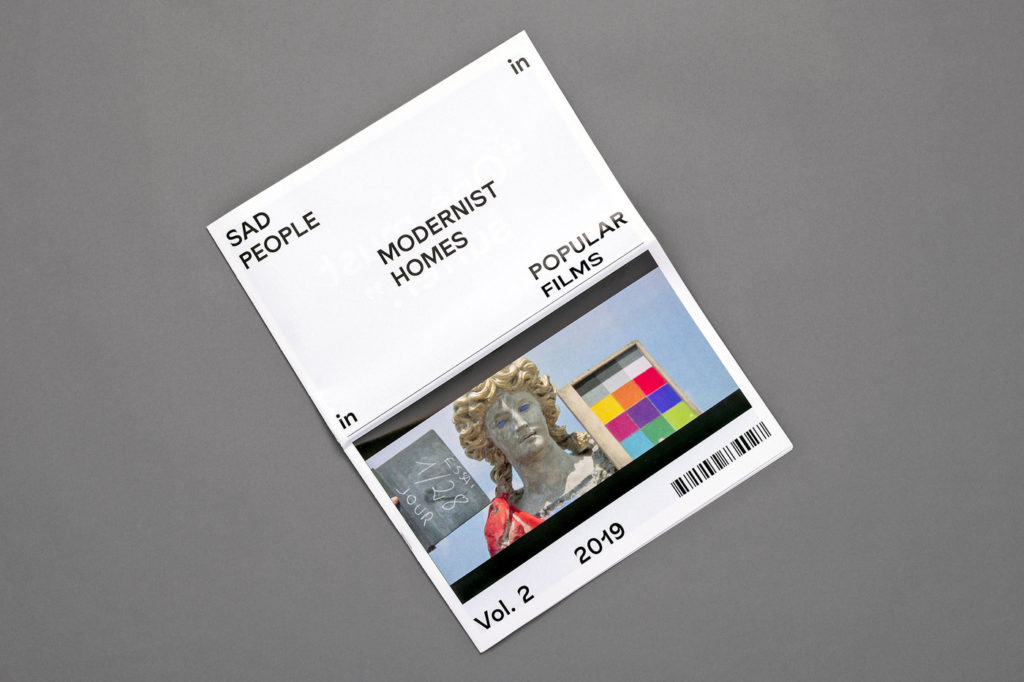

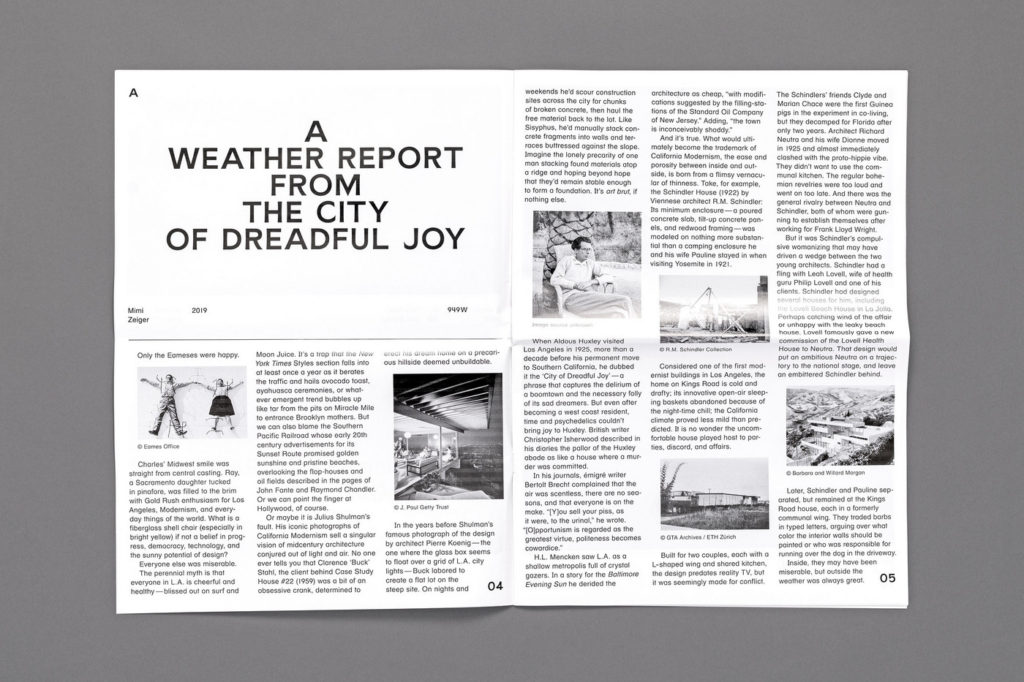

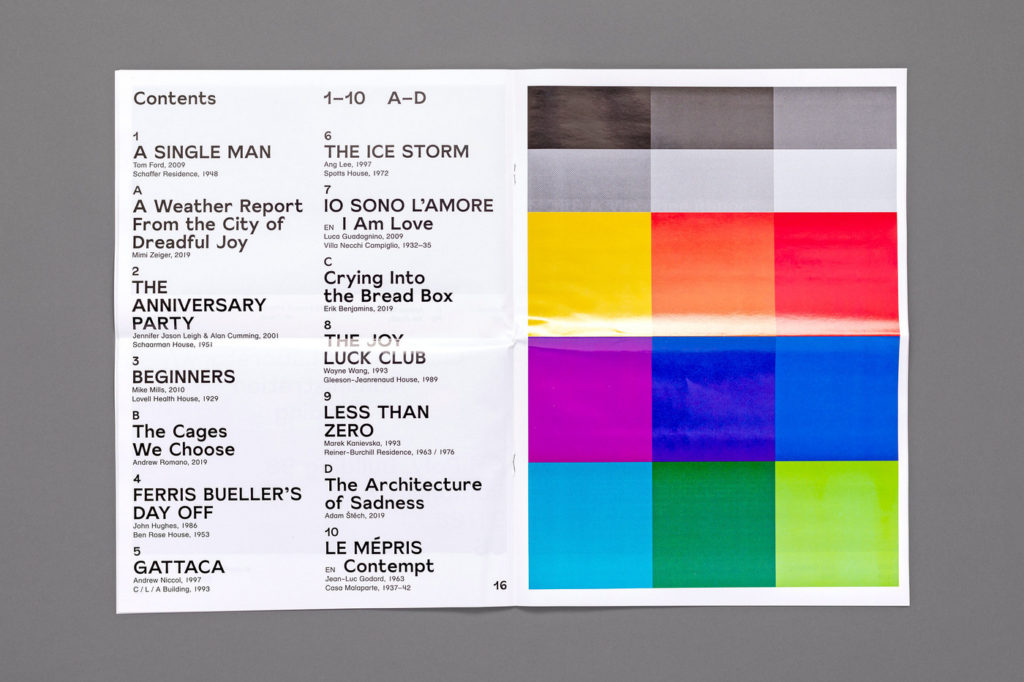

The long-awaited follow-up to the now-canonical ‘Evil People in Modernist Homes in Popular Films’ (2010), ‘Sad People’ examines the filmic trope of housing unhappy characters inside of modernist architecture.

Case studies via ten characters / homes / films, from Colin Firth’s George Falconer inside John Lautner’s Schaffer Residence in Tom Ford’s ‘A Single Man’ (2009) to Brigitte Bardot’s Camille Javal inside Adalberto Libera’s Casa Malaparte in Jean-Luc Godard’s ‘Le Mépris’ (1963).

Color imagery throughout. Essays by Erik Benjamins, Andrew Romano, Adam Štěch (Okolo), and Mimi Zeiger. Ed. by Benjamin Critton. Featuring the forthcoming type release ‘Sunset’ (late 2019).

- 258mm × 352mm

- 36 page stapled and folded publication

- Heat-set web lithography

- Edition of 2000